A

critical review of creation, diffusion, transfer and application of Knowledge

and knowledge value chain Management for SMEs in Taiwan

一個評論性探討之知識創造,擴散,轉移及應用與知識價值鏈管理為中小企業在台灣

作者:國立南澳洲大學企管博士候選人

陳德富

學校:國立南澳洲大學國際管理研究所博士班

Author:

Chen Der Fu

Candidate

of Doctor of Business Administration, International Graduate School of

management, National University of South Australia

Email:

promise_future@sinaman.com; ia2001@pchome.com.tw

Abstract

This study deals

with a field, which gets little or no attention in the research done into

knowledge management for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Taiwan. In

the first part of the study a conceptual model will be developed. This model can

be used to analyse the most important knowledge management processes (from

knowledge creation to its application) in corporation, a quantum of knowledge

progresses through four primary stages: creation, diffusion, transfer and

application of knowledge. The attention that SMEs pay to this progression

usually depends on the potential economic return associated with the quantum of

knowledge in question. In a knowledge-intensive industry, such as the high-tech

industry in Taiwan, incredible variation exists across firms in terms of the

systems they have in place to manage the progression of knowledge along this

chain. Even in a fiercely competitive industry like the high-tech industry where

product life often ranges from one to two years, within an industry, innovation

requires a firm to create knowledge and package it into concepts that lead to

the development of new products or processes. And we consider these concepts to

be useful ideas. This progression can be thought of as occurring through a

knowledge chain management (KCM). To help define some of the considerations that

firms face when developing their strategy for knowledge management, this paper

examines the link of the chain: how knowledge progresses

from creation to applications and what is the gaps

between them?

In

the second part of the study, a new framework for thinking about knowledge

creation and application is proposed and evidence of knowledge value chain

management is presented through an examination of literature theory citations to

practice. The first aim was to provide a framework for the discussion of KM with

value chain which will minimize confusion and allow for common understanding

among those activities and making KM value added in organizations. The emphasis

of this KVC (knowledge value chain) will be on the business applications of the

various KM value creation options. The second aim was to provide a checklist of

KM applications and technologies, Which can be used to assess an organization's

current level of KM performances and then plan and communicate future KM

implement in SMEs.

KCM

and KVC have been successfully applied in this capacity as an assessment and

strategic planning tool. The paper covers the KCM and KVC's theoretical

foundation, overviews the major components of the model, discusses how the KCM

and KVC can be used as a tool to assess and inventory an organization's current

KM-related investments and reviews its use as a strategic planning tool. The KCM

and KVC were developed in response to these questions. There are a number of

aims in writing this paper and in proposing the KCM and KVC as a framework for

understanding KM applications and technologies.

Finally,

I propose an integral KM model to use some simple presentations for enterprise

to use easy to follow models (input-knowledge process-output) and to illustrate

the process of knowledge creation, diffusion, transfer and application. The

procedures of all KM implement process are very detail and something new and

creative, only to link corporate strategy with KM and practice it into corporate

operation process (David J. Collis, Cynthia A. Montgomery, 1997), to form

Knowledge capabilities as the focus of organizational development and strategy

(Dawson, R., 2000). Thus KM initiative just can implement successfully. The

knowledge management processes which have the greatest effect on operational

processes are those for the creation of knowledge, diffusion, transfer and

sharing of knowledge and the embedding and application of knowledge.

The

study develops an integrated KM model for SMEs to further apply KM and to find

out what suitable KM strategies and processes can increase productivity,

employees’ satisfaction, customer satisfaction, improving quality of service

and product, reduce operating cost, accelerating technology & innovation

speed and increasing cooperation with suppliers etc. Through this model can

create a more detail, practice and completely KM structure and strategy for SMEs

in Taiwan.

How

to implement an optimal KM strategy and processes are not depending on corporate

scale (which is smaller, medium or large enterprise) but depending on corporate

core competence (i.e. handling and achieving abilities of customer satisfaction,

professional abilities, computerized degree, e-business degree, employees’

learning abilities, etc.) and interaction between technologies, technique and

corporate culture.

Keywords: KM,

KCM, KVC, KM performance, SMEs

摘要

本研究乃關於一個較少或沒人注意的領域:知識管理為中小企業在台灣,第一部份將發展一個觀念性的模型,此模型可用來分析大部分的知識管理流程

(從知識創造到應用)在企業中。一定量的知識進展經由四個階段:知識的創造,擴散,轉移及應用,中小企業注意到這些進展通常依賴潛在的經濟報酬與知識的量子之關聯在問題中。在一個知識密集的產業中如台灣的高科技產業,難以置信的變化以他們擁有的系統存在跨公司間,在適當的位置上沿著一條鏈去管理知識的進展。甚至在一個猛烈競爭產業如高科技產業,其產品生命週期經常是一到二年之範圍。在一個產業中,創新需要一家公司去創造知識及包裝它進入觀念中,去引領新產品或流程的發展,我們考慮這些觀念將會是有用的構想。這些進展可視為發生經由一知識鏈管理。為幫助定義一些考慮事務當企業面臨發展知識管理策略時,本研究檢驗知識鏈的連結:知識的進展如何從創造到應用與何者是它們之間每一個進展流程的缺口?

在本研究第二部份提議一個新架構:知識價值鏈管理,呈現經由文獻理論到實務的檢驗。第一個目的是提供一個架構為知識管理與價值鏈的討論,它將最小化困惑及允許為共同的理解在那些活動亦即使知識管理在組織中增值。知識價值鏈的影響將在不同的知識管理的價值創造功能之企業應用。第二個目的是提供一個知識管理應用及科技的檢查表,它能用於評估目前的KM績效與計劃溝通未來的KM實施在中小企業中。

KCM與KVC曾被成功的應用在當成一個績效評估及策略與流程規劃工具之容量,本研究涵蓋這二個範圍的理論基礎,綜述此模型之組成及討論KCM與KVC如何能被用做一個工具去估量及盤存一個組織的目前的KM相關投資及績效與重新探討它的使用當作一個策略規劃工具,此二理論被發展用來回應這些問題。寫此論文還有一些目的是在提議它們當成一個架構去了解KM之應用,科技與實施。

最後,我提議一個整合KM模型去使用一些簡單的展現,成為企業的容易跟隨模型(輸入-知識流程-輸出),與闡釋知識創造,擴散,轉移及應用之流程。這些KM所有的實施流程的程序是非常詳細且有一些新穎與創意,唯有連結企業的策略、流程與KM及落實它進入企業之營運流程

(David J. Collis, Cynthia A. Montgomery, 1997),形成知識能力當成組織發展及策略之焦點

(Dawson, R., 2000)。如此,KM的初始實施活動才能成功實行。而這些知識管理流程在組織流程中有最大的結果影響是那些活動為知識的創造,擴散,轉移,分享,栽種及應用。本研究發展一個整合KM模型為中小企業去進一步應用KM及找出何種適合的KM策略及流程能提高生產力、員工滿意度及顧客滿意度、改善服務及產品品質、降低營運成本、加速科技創新速度與增進與供應商的合作等等,經由此模型能創造一個更詳細的,實務與完整的KM架構及策略為台灣中小企業。

如何實施一個最適化的KM策略及流程並非依企業規模大小而定,但是依企業核心能力(如:處理及完成顧客滿意的能力、專業能力、電腦化程度,企業e化程度、員工之學習能力等等)及科技、管理技術與企業文化之互動而定。

關鍵字:知識管理,知識鏈管理,知識價值鏈,KM績效,中小企業

1.

Introduction

When,

in the early 1600s, Francis Bacon said: "Knowledge is power", we

imagine he was referring to the knowledge and power of individuals. Almost four

centuries later, we have begun to recognize how organizations, too, can succeed

or fail on their ability to effectively use and manage their "knowledge

capital" of data, information and knowledge.

Stepping

into 21st, whatever large or small enterprises all think about how to

implement knowledge management for increasing productivity, performance,

customer satisfaction and reducing operation cost. While the current literature

provides insight into the KM (knowledge management) strategies adopted by some

large organizations, most organizations differ from the large multinational

corporations (MNCs) from which KM principles have been drawn. Other than

differences in the number of personnel, they tend to be regionally or locally

focused, have a narrower scope of business, and have less financial and

administrative "slack". The management, who are often the owners of

these firms, tending to focus on the core business of their organizations and

pay less attention to other issues.

Most

of these organizations cannot afford (or do not want to commit to) the expensive

consultancy services used by larger firms. Few have dedicated information

professionals on staff. Many of them may be unaware of the potential of KM since

the KM "industry" looks primarily towards those larger organizations

with large budgets for consulting and technology. Small organizations can

benefit from attention to knowledge management. Their greatest acknowledged need

is for effective "knowledge repositories". The owners and managers of

many small organizations are just beginning to identify how information and

knowledge management may assist them. The availability of appropriate

technologies will make the value of knowledge management more tangible, as it

has in larger organizations. Small organizations, though, can seldom afford the

cost of being leaders in technology adoption, or of trial and error in

implementation. They will rely heavily on consultants and information

professionals for success, they should have sufficient sensitivity to

organizational culture and practices to design and implement systems that can be

embedded in daily activities. Finally, they must link and interact between

technology, people and technique.

In

past, Taiwan created admired economic miracle through superior productive system

and management ability. Nevertheless, following large environment and basic

conditions changing, recently, Taiwan faces the dilemmas of rising productive

cost and corporate moving out, especially after Mainland China a serious of

reforming and openness, their market’s quality and quantity all have

remarkable raising, and to form future places which most development potential

in global corporate development blueprint, furthermore, to make large pressure

to Taiwan industries. Therefore, Taiwan must seek actively the new positioning

and role in global industrial value chain.

There

are 95 % industries in Taiwan are small-medium sized enterprises (SMEs),

especially, even there are 80 % of them are traditional industries. Especially

now, Taiwan also faces the three mainly problems: 1. The recession of national

economic 2.Traditional industries need turn around 3. Industries shift out to

Mainland China, Therefore, domestic economy is worse and worse, unemployment

problems are serious increasingly. For solving these problems, Taiwan government

throws their whole being into advocate knowledge economy to help SMEs turn

around to knowledge enterprises and hope the root of enterprises can keep

staying in Taiwan, and doing their best to avoid all of enterprises move into

Mainland China, because that will cause more serious unemployment problems in

Taiwan.

If

the SMEs, especially those traditional industries want to sustained management

and not to be eliminate through competition, they must turn around from past

"labor density" and to current

"technology density" and "knowledge density", and launch to

implement Knowledge Management (KM), it seems that is the unique outlet for

Taiwan industries. After national economy to be revived again, Taiwan will

re-create economic miracle.

Josephine

Chinying Lang (2001) proposed five hindrances to knowledge creation and

utilization in organizations: First, there may be inadequate care of those

organizational relationships that promote knowledge creation. Second, there may

be insufficient linkage between knowledge management and corporate strategy.

Thirdly, inaccurate valuation of the contribution that knowledge makes to

corporation's bottom line renders the value of knowledge management ambiguous.

Fourthly, there may be a pervasive lack of holism in knowledge management

efforts. Finally perhaps not something ordinarily considered a problem for

managers to deal with poor verbal skills may hinder the actual processes of

knowledge. The task of knowledge management is to identify such barriers and to

overcome them.

For

achieve objectives of the study and to solve several barriers for knowledge

creation, diffusion, transfer and application in organizations exist when SMEs

implement KM. According above reasons and through a preliminary literature

review, the study summarizes, reviews and criticizes the literatures to focus on

developing two models:

1.The

knowledge chain management- the creation, diffusion, transfer and application of

knowledge.

2.The

knowledge value chain - knowledge management must match corporate operating

process and along corporate value chain to create value for customers, thus KM

just can achieve end of corporate goal: customer satisfaction, and due to this,

corporation can develop a really suitable strategy and process for themselves.

Under

these two models, scholars and practitioners argued that the greatest challenge

for the manager of intellectual capital is to create an organization that can

share the knowledge and measure KM performance. When skills belong to the

company as a whole, they create competitive advantages that others cannot match

(Stewart, 1997).

Next,

the study will emerge a detail literature review from definition and characters

of knowledge, various definitions of KM, knowledge chain and knowledge value

chain management, integrated conceptual KM models for SMEs and KM performance

measurement as following:

Defining

knowledge accurately is difficult. However, it is well agreed that knowledge is

an organized combination of ideas, rules, procedures, and information. In a

sense, knowledge is a "meaning" made by the mind (Marakas, 1999, p.

264). Without meaning, knowledge is inert and static. It is disorganized

information. It is only through meaning, information finds life and becomes

knowledge.

What

is the difference between data, information and knowledge?

This

is a term which is very easy to be confused by people so far, Information and

knowledge are distinct based on their internal organization. Information is

disorganized, while knowledge is organized (Koniger and Janowitz, 1995). The

distinction between information and knowledge depends on users' perspectives.

Knowledge is context dependent, since "meanings" are interpreted in

reference to a particular paradigm (Marakas, 1999, p. 264).

In a sense,

knowledge is a "meaning" made by the mind (Marakas, 1999, p. 264).

Without meaning, knowledge is information or data. It is only through meaning,

that information finds life and becomes knowledge (Bhatt, 2000a).

Beijerse

(1999, 2000) define knowledge here as follows: “Knowledge is seen here as the

capability to interpret data and information through a process of giving meaning

to these data and information; and an attitude aimed at wanting to do so. New

information and knowledge are thus being created, and tasks can be executed. The

capability and the attitude are of course the result of available sources of

information, experience, skills, culture, character, personality, feelings,

etc.”

Knowledge

are combination of data and information and learning

Cohen and

Levinthal (1990) explain this fact in arguing that knowledge expansion is

dependent on learning intensity, and prior knowledge. In other words,

accumulated prior knowledge increases the ability to accrue more knowledge and

learn subsequent concepts more easily. Therefore, we argue that knowledge is an

organized combination of data, assimilated with a set of rules, procedures, and

operations learnt through experience and practice.

Knowledge

are capability and action

Murray

(http://www.ktic.com/topic6/13_term2.html) says for instance: "Knowledge is

information transformed into capabilities for effective action. In effect,

knowledge is action." This aspect of capabilities resulting from

information is something we also see at Weggeman (1997), but he adds some other

aspects: "Knowledge is a personal capacity that should be seen as the

product of the information, the experience, the skills and the attitude which

someone has at a certain point in time".

Explicit

vs tacit knowledge

This difference

was first introduced by the Hungarian chemist, economist and philosopher Michael

Polanyi. He stated that personal or tacit knowledge is extremely important for

human cognition, because people acquire knowledge by the active (re)creation and

organization of their own experience (Polanyi, 1966). Tacit knowledge is that

knowledge which cannot be explicated fully even by an expert and can be

transferred from one person to another only through a long process of

apprenticeship. Polany's famous dictum, "We know more than we can

tell", points to the phenomenon in which much that constitutes human skill

remains unarticulated and known only to the person who has that skill. Tacit

knowledge is the skills and "know-how" we have inside each of us that

cannot be easily shared (Lim, 1999).

Tacit

knowledge evolves from people’s interactions and requires skill and practice.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) suggested that tacit knowledge is hidden and thus

cannot be easily represented via electronics. Tacit refers to hunches,

intuitions and insights (Guth, 1996), it is personal, undocumented,

context-sensitive, dynamically created and derived, internalized and

experience-based (Duffy, 2000).

Figure 2-1 shows that one

of the main constituents of organizational knowledge is

"interactions". In an organization where the number of interactions

between organizational members is kept to a minimum, most of knowledge remains

in the control of individuals rather than the organization. However, a large

part of knowledge is internalized within the organization through informal

get-together and interactions between employees (Bhatt, 1998). In this

interactive process, not only do individuals enrich their knowledge, but also

make a part of knowledge available for the organization that is generated as a

result of the interactions. In other words, the knowledge that is internalized

within the organization is not produced by any of the organizational members

alone, but created through their interactions.

Figure 2-1:

Relationship between individual knowledge and organizational knowledge

2.2

What is knowledge management?

Process

viewpoint

KM

is the process of creating, capturing, and using knowledge to enhance

organizational performance; KM is the management of the information, knowledge

and experience available to an organization─its

creation, capture, storage, availability and utilization─

in order that organizational activities build on what is already known and

extend it further (Mayo, 1998).

A common definition of KM

is: "The collection of processes that govern the creation, dissemination

and leveraging of knowledge to fulfill organizational objectives". KM is a

framework within which the organization views all its processes as knowledge

processes. (Ching Chyi Lee, Jie Yang, 2000)

Organizational view

KM

is about encouraging individuals to communicate their knowledge by creating

environments and systems for capturing, organizing, and sharing knowledge

throughout the company, Thomas M. Koulopoulos and Carol Frappaolo (2001) used

‘knowledge management is bring collective intelligence influence ability into

full play, to increase enterprise response and innovation ability as a concise

definition. An organization’s work with KM should focus on transposing tacit

knowledge into explicit knowledge and see to it that individual knowledge

becomes organizational knowledge. This can be explained not only by a need for

organizations to better manage knowledge by establishing core competencies for

individuals, judging success and performance indicators via recognition of

invisible assets, but also for organizations to strive to become an innovative

organization and a learning organization with a knowledge sharing culture

Value viewpoint

Sveiby

(http://www.sveiby.com.au/ knowledgemanagement.html) for instance puts the

emphasis on intangible assets when defining knowledge. He therefore defines

knowledge management as "the art of creating value from an organization's

intangible assets". Beijerse (1999) developed the definition of knowledge

here puts more emphasis on the importance of tacit knowledge, and he saw this as

its added value. He defined knowledge management as follows: “Knowledge

management is achieving organizational goals through the strategy-driven

motivation and facilitation of (knowledge-) workers to develop, enhance and use

their capability to interpret data and information (by using available sources

of information, experience, skills, culture, character, personality, feelings,

etc.) through a process of giving meaning to these data and information.”

KM

is an emerging set of organizational design and operational principles,

processes, organizational structures, applications and technologies that helps

knowledge workers dramatically leverage their creativity and ability to deliver

business value. In fact, KM is about people and the processes they use to share

information and build knowledge (Hanley, 1999).

People,

technology and knowledge viewpoint

Arthur

Andersen consulting group (1999) have defined KM= (P+K) S, P is

people (knowledge loader), K is knowledge (include data, information, knowledge

and intelligence), S is share, + is technology, this formula means KM structure

includes organizational co-sharing, application and practice. Information

technology (+) can help to construct KM and to accelerate the process of KM.

System

view

KM is mean

“enterprise build a management system for apply effective knowledge capitals,

accelerate products or services innovation, the system include knowledge

creation, knowledge circulation and knowledge value added three functions.”

(Se-Hwa Wu, 2001)

Strategy,

structure, culture and system viewpoint

KM is the

management of information within an organization by steering the strategy,

structure, culture and systems and the capacities and attitudes of people with

regard to their knowledge. KM includes the entirety of systems with which the

information within an organization can be managed and opened up (Beijerse,

2000).

Knowledge

Management interacts between technologies, techniques and people

Knowledge

management shapes the interaction pattern between technologies, techniques, and

people. For instance, IT can capture, store, and distribute information quickly,

but it has its limit on information interpretation. Organizations which have

been successful in obtaining long-term benefits from knowledge management, are

found to carefully coordinate their social relations and technologies (Bhatt,

1998).

Technological

solutions can be captured and grafted. But to manage knowledge, organizations

need to construct an environment of participation, coordination, and knowledge

sharing. In general, implementing knowledge management programs requires a

change in organizational philosophy.

In sum, KM focuses on

"doing the right thing" instead of "doing things right", KM

is a framework within which the organization views all its processes as

knowledge processes (Ching Chyi Lee, Jie

Yang, 2000). Therefore, the study review and criticize knowledge chain

management and knowledge value chain as follows:

2.3

Knowledge chain management

Beijerse

(1999, 2000) define knowledge here as follows: “Knowledge is seen here as the

capability to interpret data and information through a process of giving meaning

to these data and information; and an attitude aimed at wanting to do so. New

information and knowledge are thus being created, and tasks can be executed. The

capability and the attitude are of course the result of available sources of

information, experience, skills, culture, character, personality, feelings,

etc.” He didn’t point out what detail about “through a process of giving

meaning to these data and information” in his definition for knowledge, and

Bassie (1997) didn’t propose complete process and how to link gap of each part

of knowledge chain flows, Melissa M.

Appleyard, Gretchen A. Kalsow (1999) in their study presents a new

framework for thinking about knowledge diffusion within an innovative community.

They define innovation as the operationalizing of new ideas, and they define

knowledge diffusion as the movement of useful ideas between organizations.

Within an industry, innovation requires a firm to create knowledge and package

it into concepts that lead to the development of new products or processes, and

they consider these concepts to be useful ideas. This progression can be thought

of as occurring through a knowledge chain management (Figure 2-2).

Therefore,

this study deals with a field, which gets little or no attention in the research

done into knowledge chain management, In the first part of the study a

conceptual model (knowledge chain management (Figure 2-3) will be developed.

This model can be used to analyze the most important knowledge management

processes in corporation. The model is used for analyzing from knowledge

creation to its application, a quantum of knowledge progresses through four

primary stages: creation, diffusion, transfer and application of knowledge. The

attention that firm pay to this progression usually depends on the potential

economic return associated with the quantum of knowledge in question. In a

knowledge-intensive industry, such as the high-tech industry in Taiwan,

incredible variation exists across firms in terms of the systems they have in

place to manage the progression of knowledge along this chain. Even in a

fiercely competitive industry like the high-tech industry where product life

often ranges from one to two years, within an industry, innovation requires a

firm to create knowledge and package it into concepts that lead to the

development of new products or processes. And we consider these concepts to be

useful ideas.

For

more complete to describe knowledge flow in the chain, here I propose a modified

model as figure 2-3, from knowledge creation, diffusion, transfer to

application, some firms can further to make knowledge innovation, some firms can

reuse knowledge to form a feedback to create new knowledge. Thus knowledge will

form a cyclic circulation to accumulate knowledge.

In

the whole process of KM, the innovation activity fits the product

differentiation strategy, which can enable corporation gains the

competitiveness, while reusing knowledge fits low cost strategy, by which

competitiveness gained again. Generally, managing knowledge assets should, like

patents, trademarks and licenses, even add knowledge to the balance sheet.

Figure 2-3: The knowledge chain

Source:

modified from Melissa M. Appleyard, Gretchen A. Kalsow, 1999

To

help define some of the considerations that firms face when developing their

strategy for management of knowledge to increase production, reduce cost and

increase customer satisfaction, this study examines the link of the chain: how

knowledge from creation to applications and what is the gaps between them? To

fill the gaps for the successful management of this knowledge chain becomes a

distinguishing characteristic of leading firms, particularly in a

knowledge-intensive industry like the semiconductor industry. A firm's stock of

useful ideas, its technical prowess, depends not only on its internally

generated ideas, but also on the absorption of ideas that originate outside of

its boundaries. Therefore, this study also examines the flow of useful ideas

between firms and constructs a new framework for the forces that drive knowledge

creation, distribution (diffusion), transfer to application.

2.4

The knowledge value chain

Another

good example of the link between the definition of knowledge and the way to look

at the management of knowledge is the work of Mathieu Weggeman (1997). Central

to Weggeman's work is "the knowledge value chain". In the process of

knowledge management, Weggeman distinguishes four successive constituent

processes (Figure 2-4).

First,

the strategic need for knowledge needs to be determined. Second, the knowledge

gap needs to be determined. This is the quantitative and qualitative difference

between the knowledge needed and that available in the organization. Third, this

knowledge gap needs to be narrowed by developing new knowledge, by buying

knowledge, by improving existing knowledge or by getting rid of knowledge that

is out of date or has become irrelevant. Fourth, the available knowledge is

disseminated and applied to serve the interest of customers and other

stakeholders.

It

is important to notice that knowledge management here does not refer to

information technology only. Attention is also being paid to strategic,

personal, organizational and cultural aspects, which are at least as important

as the technological side of the story. With this in mind, Weggeman defines

knowledge management as "arranging and managing the operational processes

in the knowledge value chain in such a way that realizing the collective

ambition, the targets and the strategy of the organization is being

promoted".

Knowledge

value chain model

One

good more example of the link between the definition of knowledge and the way to

look at the management of knowledge is the work of Ching Chyi Lee and Jie Yang

(2000). Central to their work is also "the knowledge value chain". In

the process of knowledge management, Lee and Yang distinguishes five successive

constituent processes (Figure 2-5: Knowledge

value chain model).

1. knowledge acquisition:

Organizational information acquisition through searching can be viewed as

occurring in three forms (Huber, 1991):

(1)

scanning; (2) focused search; and (3) performance monitoring.

1.

knowledge innovation:

(1) from tacit knowledge

to tacit knowledge, which is called socialization;

(2) from tacit knowledge

to explicit knowledge, or externalization;

(3) from explicit

knowledge to explicit knowledge, or combination; and

(4) from explicit

knowledge to tacit knowledge, or internalization.

3.

knowledge protection: (1) legal and IT protection (2) corporations should

contract with employees regarding confidential information and their tenure in

case of they leave (3)develop other protocols and policy guidelines which

recognize and promote rights of knowledge (4) and then implement them by staff

awareness and education campaigns.

4.knowledge integration:

This cumulative manufacturing, sales, and service experiences from

different departments, together with information gathered from outside sources,

can be integrated into the KVC of the organization, which is a inter-sub-KVC

integration process, eventually being the base of KM infrastructure.

5.knowledge

dissemination: (1) through systematic transfer: to create a knowledge-sharing

environment (2) to show its commitment for sharing knowledge (3) to foster the

employee's willingness to share and contribute to the knowledge base. (4) Reward

structures and performance metrics need to be created which benefit those

individuals who contribute to and use a shared knowledge base. (5) Those who

excel at knowledge sharing should be recognized in public forums such as

newsletters and e-mails. (6) By effective communication.

Differences

among competitor value chains are a key source of competitive advantage. In

competitive terms, value is the amount customers are willing to pay for what a

corporation provides them. Value is measured by total revenue, a reflection of

the price a corporation's product commands and the units it can sell. A firm is

profitable if the value it commands exceeds the costs involved in creating the

product (Porter, 1985). Creating value for customers that exceeds the cost of

doing so is the goal of any competitive strategy. Value, instead of cost, must

be used in analyzing competitive position since corporations often deliberately

raise their cost in order to command a premium price via differentiation.

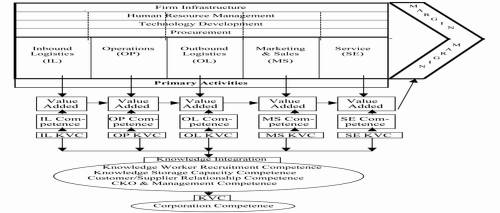

Employing Porter's value chain analysis approach, we developed a knowledge value

chain model.

Knowledge

value chain consists of KM infrastructure (CKO & management, knowledge

worker recruitment, knowledge storage capacity, customer/ supplier relationship)

and the KM process's activities and knowledge performance. These infrastructure

components and activities are the building blocks by which a corporation creates

a product or provides service valuable to its customers. Knowledge performance

can be measured in two categories (van Buren, 1999). One is financial

performance. However, financial assessments such as ROI are particularly

difficult to make for KM activities. The other is non-financial measures

including operating performance outcomes and direct measures of learning.

Examples of operating performance measures include lead times, customer

satisfaction, and employee productivity. Learning measures include such items as

the number of participants in communities of practice, employees trained, and

customers affected by the use of knowledge.

As

the value chain itself implies, each element of activity can create value and

then all the value flows to the endpoint of the business value chain and joins

together, forming the overall value of business, which is usually expressed as a

margin (see Figure 2-6).

|

Figure 2-6: Relationship between

business value chain and KVC

Source: Ching Chyi Lee and Jie Yang

(2000)

By

analyzing the above, we might note that competence is after all the measurement

of each sub-KVC. That is the reason why we feel that the core competence of the

corporation should be employed as the key non-financial measure of knowledge

performance.

KM

is a process that transforms information into knowledge, KM guides the way a

corporation performs individual knowledge activities and organizes its entire

knowledge value chain. It is suggested that competitive advantage grows out of

the way corporations organize and perform discrete activities in the knowledge

value chain, which should be measured by the core competence of the corporation

(Ching Chyi Lee, Jie Yang , 2000). In the end, we would raise another assumption

for further discussion, so that for KM to "open the black box" of a

corporation and examine its intricate details. We assumed that the corporation

should be treated more or less as a box of tricks producing the predictable

outputs of knowledge-based products and services from specific inputs of

information or/and knowledge.

For

better to understand details of knowledge in knowledge chain management and KVC,

there are detailed descriptions (from knowledge creation, distribution, transfer

to application) in next sections.

2.5

knowledge creation

Even though some researchers argue that knowledge creation is basically

an individual thought process (e.g. Crossan et

al., 1999), some others have recently shown that creativity can be learnt

and taught (Marakas and Elam, 1997). In either case, we believe that knowledge

creation in the organization is led through individuals, i.e. an organization

creates knowledge through its individuals, who learn and generate new

“realities” by breaking down rigid thinking and assumption (e.g. Argyris and

Schon, 1978).

Knowledge creation is not a systematic process that can be planned and

controlled (Lynn et al., 1996; Mayo,

1959, p. 59). The process is, rather, continuously evolving and emergent.

Motivation, inspiration, and pure chance play an important role in knowledge

creation. The success of knowledge creation is a chance event, based on the

convergence of the world reality and the structure of one's thinking (Horgan,

1996). Creation is only a fearful possibility of finding a meaningful relation

in uncovered combinations (Horgan, 1996, p. 153).

The

knowledge creation process is evaluated based on its originality and adaptive

flexibility to facilitate the solution of a problem in different contexts. The

process of knowledge creation and evaluation not only requires organizations to

alter their cognitive frameworks (Weick, 1979), but also forces organizational

members to view reality in new perspectives (Weick, 1995).

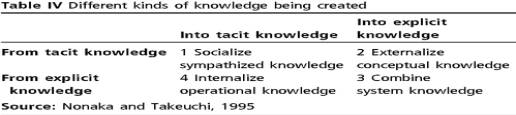

Nonaka

& Takeuchi(1995)assume

organizational knowledge creation that is a spiral process , call as

‘knowledge spiral’ (Table 2-1).

|

Moreover,

knowledge creation start from individual layer, raise more and more and enlarge

interaction range, diffuse from individual to community, organization even

inter-organization. Therefore, knowledge creation diffuses more and more from

individual layer to community, organization, last to external organization. In

process, constant knowledge integration activity exists among socialization,

externalization, combination and internalization. Therefore, four different

kinds of knowledge are being created, over and over again.

Leonard-Barton

(1995, 1998) assume there are four items of knowledge creation:

1.

Shared Problem Solving: now

2.

Implementing & Integrating: inside

3.

Experimenting & Prototyping: future

4.

Importing Knowledge: outside

Knowledge

creation activity is get through above four activities, and accumulate or create

out core competence.

2.6

Knowledge diffusion

Melissa

and Gretchen (1999) defined knowledge diffusion as the movement of useful ideas

between organizations. Knowledge needs to be distributed and shared throughout

the organization, before it can be exploited at the organizational level (Nonaka

and Takeuchi, 1995). In reality, distribution and sharing knowledge is not an

easy task (Davenport, 1994). To what extent a firm succeeds in distributing

knowledge depends on organizational culture and the amount of explicit knowledge

available in the firm.

An

organization relying on traditional control and authority relationships finds it

difficult to distribute knowledge. Because a management mentality on supervision

and order often limits the opportunities for the formation of social-units and

groups to come together, considered necessary to convert individual knowledge to

organizational knowledge (Argyris and Schon, 1978; Huber, 1991). If knowledge

distribution channels are informal, developed based on trust and cooperation,

knowledge distribution can be quicker and honest, and consequently, it can be

put to a higher level of scrutiny.

Easy

degree of knowledge diffusion influence by amounts and high and low layers of

co-knowledge very large, the more and higher layers of organizational

co-knowledge then the easy for organizational knowledge diffusion.

Common

knowledge is one of necessary key factor of KM, Grant(1996)assume

knowledge diffusion depend on common knowledge. Co-knowledge include common

knowledge elements to all organizational members, like Nonaka & Takeuchi(1995)submitted

‘redundancy’, that is overload information need for organizational members

operation, make person can enter other’s function border.

Grant(1996)sort

five layers for common knowledge style in his study:

1.

Common language

2.

Other style of symbol communication

3.

Expertise knowledge of common base

4.

The meaning of co-sharing

5.

Recognize of personal knowledge domain .

In

practice, enterprise can through project-groups, team-cooperation or

master-slave way to diffuse individual knowledge to participate more and more,

in advance to diffusion into organization-wide. Some enterprises even through

internal training way to normalize knowledge diffusion.

Knowledge

diffusion strategy

The

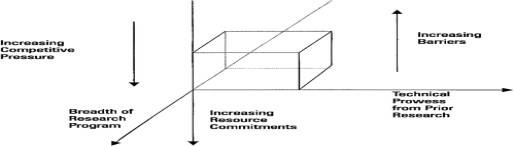

depiction of the current-like nature of knowledge diffusion is presented in

figure 2-7, Melissa M. Appleyard, Gretchen A. Kalsow (1999) assumed

that a firm's position depends on its technical prowess, or the aggregation of

the experiences of the inventors it employs and other resource commitments.

Knowledge diffusion between firms can be thought of as a particle in the current

moving from one firm's position to another. Melissa M. Appleyard, Gretchen A. Kalsow (1999) hypothesize

that the attractive forces across firms with similar technical prowess overpower

the forces attracting companies with dissimilar technical prowess. In Figure

2-7, the arrows demonstrate the internal and external forces at work, and their

hypothesis suggests that knowledge should diffuse more readily across

organizations with similar attributes, i.e. in the same location of a

technological current.

Figure

2-7: The fluid dynamics framework of knowledge diffusion

Source: Source: Melissa M.

Appleyard, Gretchen A. Kalsow, 1999

2.7

Knowledge transfer

According

to Marshall et al. (1996), this implies the transfer of knowledge and expertise

throughout the organization within departments, plants, and countries and across

national borders. As Garvin (1993) suggests, for learning to be more than a

local affair, knowledge must be developed, retained and spread effectively

throughout the organization, on a national as well as global scale. New

knowledge is created by people who share and transfer their knowledge and

expertise throughout the organization from individual to individual, individual

to a team or group, team or group to individual, or team or group to team or

group.

According

to Davenport and Prusak (1998, p. 101), the transfer of knowledge then involves

both the transmission of information to a recipient and absorption and

transformation by that person or group. To be of value to the organization, the

transfer of knowledge should lead to changes in behavior, changes in practices

and policies and the development of new ideas, processes, practices and

policies. This makes it imperative for organizations to secure the efficient use

and application of the transferred knowledge. The successful transfer of

knowledge and expertise then around a business requires not just the

establishment of networks but also the transfer of people. People have to be

moved in order to get deep-seated, deep-routed ideas and knowledge into

circulation and to understand particular operations in specific locations (Prusak,

1998).

When

organization cognize lack of some knowledge within organization, it will produce

“knowledge gap”, therefore organization need bring in or transfer into

knowledge. Gilbert & Gordey-Hayes (1996)submit five stages mode of knowledge

transfer as follow:

1.

Acquisition

2.

Communication

3.

Application

4.

Acceptance

5.

Socialization

Gilbert

& Gordey-Hayes (1996) assumed knowledge transfer does not happen statically,

it must through constant dynamic learning just can reach goal. Besides, Harem,

Von Krogh & Roos (1996) assume knowledge concept of knowledge transfer

process can separate as four categories, have or not of these knowledge will

affect degree of knowledge transfer:

1.

To understand scarce knowledge

2.

To know knowledge about others’ knowledge

3.

Behavioral knowledge

4.

Task-oriented knowledge.

Nonaka

& Takeuchi(1995)from

tacit and explicit knowledge interaction gain four different knowledge transfer

mode as list below:

1.

Socialization:

from tacit to tacit through sharing experience to reach tacit knowledge transfer

process.

2.

Externalization:

from tacit to explicit, tacit knowledge through metaphor, analogy, concept,

assumption or mode to represent.

3.

Combination:

from explicit to explicit, systemization concept to form knowledge system

process, involve combining different explicit knowledge system.

4.

Internalization:

from explicit to tacit, use language, story transmit knowledge or build as

documents and manual all help for transfer explicit knowledge to tacit

knowledge.

2.8

Knowledge application

To

have value knowledge must be applied within a specific business context to

create value. This will be done differently depending on the industry, however

the underlying processes are often very similar, drawing on people with diverse

expertise and knowledge both to enhance existing value chains, and to create new

ones. Specific examples where knowledge is applied to create value include

product development, process enhancement, marketing, and all client

interactions.

Knowledge management as a management tool

KM is often described as a management tool. More precisely, it is

described either as an operational tool or as a strategically focused management

tool.

Knowledge management as an information handling tool

Knowledge

is often regarded as an information-handling problem. It deals with the

creation, management and exploitation of knowledge. Some of the literature fits

into a definition of KM that consists of separate but related stages.

Knowledge management as a strategic management tool

KM

can be seen as a way to improve performance (Ostro, 1997; Bassi, 1997),

productivity and competitiveness (Maglitta, 1995). A way to improve effective

acquisition, sharing and usage of information within organizations (Maglitta,

1995). A tool for improved decision-making (People Management, 1998; Cole-Gomolski,

1997a, 1997b); a way to capture best practices (Cole-Gomolski, 1998); a way to

reduce research costs and delays (Maglitta, 1995) and a way to become a more

innovative organization. (People Management, 1998; Hibbard, 1997)

Innovation/creation

KM applications

There

is still a role for individual innovation; however, innovations are increasingly

coming from the marriage of disciplines and teamwork. This category of knowledge

management is best summarized by Nonaka (Nonaka and Konno, 1999) when he says,

“Knowledge is manageable only insofar as leaders embrace and foster the

dynamism of knowledge creation. The innovation/creation of new knowledge is the

most popular topic in today's management literature. The focus of the business

and KM applications in this element is on providing an environment in which

knowledge workers of various disciplines can come together to create new

knowledge. The most common application referenced in the literature is the

creation of new products or company capabilities.

2.9

An integral conceptual knowledge management model for SMEs

Definition

of SMEs

Small and medium-sized companies,

meaning those that employ less than 500 people, are an economic force that

should not be neglected. In Germany, for example, much of the recent economic

growth has come from organizational form. According to statistics of the

Institut für Mittelstandsforschung, 97.9 percent of German companies fall

within this boundary, with an estimated 2.7 million jobs (41.6 percent of

Germany's current jobs) being dependent upon them. Furthermore, 36 percent of

all German industrial investments are being made by small and medium-sized firms

(Wimmer and Wolter, 2000).

The

forms of knowledge in SMEs

Small and medium-sized companies often

experience erosion of knowledge that can have many forms. The most obvious is

the leaving of a key employee, whether it is via retirement or leaving to work

for a competitor's firm. In these instances, and for smaller firms in

particular, Barchan (1999) states that:

...

you lose more than that person's knowledge. You also lose any investments you

have made in that person's professional development and competence - unless you

find ways to capture it.

Other

forms of knowledge erosion are particularly threatening to smaller firms.

Problems of succession in family-owned businesses can result in the abrupt

crippling of a company if its owner decides to quit or dies.

Aside

from these life-threatening issues, smaller companies are also often battling

the problems associated with acquisition, lay-offs, and other economic factors

that can lead to major knowledge erosion when key employees leave the company.

Retaining and acquiring knowledge in SMEs Smaller firms can employ many

techniques for retaining knowledge, these techniques include:

training;

job rotation; maintaining a repository of "lessons learned"; expansion

management;

recruiting

and human resource management; mentoring; knowledge maps; knowledge databases;

best practice sharing; customer relationship management; e-Business; intelligent

agents.

Knowledge

construction and creation (Figure 2-9) is a key element of effective KM. This

aspect of KM identifies what is constituted as knowledge and how such knowledge

is developed in the organization and its employees. Sternberg (1999) indicates

that successful SMEs are characterized by creating new knowledge within the

process of innovation. Embodiment and dissemination of knowledge is seen as

important for KM in SMEs as developing tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge

and diffusing such knowledge is essential in organizations with scarce

resources.

The

main objective of KM is its "use" or benefit (Figure 2-9). Demarest

(1997) describes "use" as ultimately "the production of

commercial value for the customer". However, Wilkinson and Willmott (1994)

argue that business improvement methods in general must widen their objectives

to embrace the mutually supporting objectives of increased business and employee

benefits. Innovation is a key "use/benefit" of KM. Henry and Walker

(1991) and Sternberg (1999) link innovation to "new knowledge" or new

constructed knowledge by showing how tacit knowledge can become explicit

knowledge.

Klobas

(1997) illustrated key relationships in a diagram, from which Figure 2-10 is

drawn.

Figure 2-10: A framework of characteristics from which to examine KM in small organizations

Source: Klobas (1997)

Several

thoughtful practitioners have developed guidelines for successful KM, putting

technology into its rightful place as an aid rather than an outcome. If an

organization's uniqueness and value are derived from its unique knowledge, there

is a need to create new knowledge and share the knowledge that exists. But

knowledge is situation-specific, and much knowledge is not shared but held by

individuals. Organizations therefore need processes and systems to promote

knowledge acquisition and knowledge sharing as well as knowledge creation.

Guidelines for KM, based on these needs, assume large, international

organizations, but differences in scale and scope of operation of smaller

organizations may result in differences in these organizations' needs for KM

processes and systems. We will therefore review prominent guidelines before

drawing on them, along with theory and practice, to develop a framework of

characteristics from which to examine KM in small organizations.

Beijerse

(2000) proposed three findings for his empirical study of SMEs:

1.

Strategy: hardly any systematic knowledge management policy on strategic level

in small and medium-sized companies

2.

Structure and culture: hardly any systematic knowledge management policy on

tactical level in small and medium-sized companies

3.

Systems: 79 different instruments with regard to knowledge management on

operational level in small and medium-sized companies

To summarize the findings,

can conclude that there is no explicit policy that is targeted at strategic

knowledge management within the 12 companies studied. Generally no goals are

included in the company strategy - if this is even formulated - with regard to

direct monitoring of available and necessary knowledge, nor of the development,

acquisition, locking, sharing, utilisation or evaluation of knowledge. This

brings with it that there is no explicit policy on a tactical level - that of

the organisation structure and company culture - in order to make the structure

facilitating to development, acquisition and locking of knowledge or to make the

culture motivating with a regard to sharing and utilising knowledge.

In

sum, current KM instruments for SMEs is enough, the urgent need of KM for SMEs

is how to measure KM performances? Next section will illustrate these

measurements as follows.

2.10

The measurements of KM performances

Organizations generally do

not sufficiently recognize knowledge contributions because the conceptualization

and measurement of knowledge capital as a primary organizational asset remains

rudimentary (Chinying Lang, 2001). Extensive traditional systems allow managers

to track their use of economic capital but such systems cannot easily

accommodate knowledge capital. Without realistic and robust measures of

knowledge capital, managers will revert to economic capital. Corporations that

are experimenting with such measures include the Canadian Imperial Bank of

Commerce, Skandia, Dow-Corning, and so on. Skandia details information such as

quality and quantity of customer relationships, training and development

investments to improve operational processes, relationships with partner firms

etc. in categories such as human focus, customer focus, process focus, renewal

and development focus, and so on. Across units, these categories are tracked in

terms of different variables tied to their strategic importance in specific

business units. The American Productivity and Quality Center in Houston is

similarly trying to track and benchmark such efforts in leading firms (Miles et

al., 1998). Suffice to say these efforts are very much in the very earliest

stages of development.

If employees are evaluated

and compensated based on what they know, it may be difficult to get them to

share their knowledge for the common good. Thus, it is important to reward

individuals for sharing knowledge and using collective knowledge. Because

Burson-Marstellar workers are compensated based on how much they can charge

clients, people have to be known across their practices in order to remain

sufficiently billable. This culture at Burson-Marstellar is also reinforced

through meetings aimed at getting geographically dispersed groups to work

together (Schwartz, 1999).

For

the measurements of KM performances, Davenport & Prusak (1998) in their

study pointed out: there are five criteria can be a successful or failed

reference for corporate KM measurement:

1.

Growth of plan relative resource includes employees and budget.

2.

Content of knowledge and growth of utilization frequency, i.e. document amount

in database, user access times, or how many people participate discussion type

database.

3.

Besides one or two people’s efforts, this plan can sustain or not? In other

words, this plan have not personal characteristic. But attribute all employees

common mission.

4.all

employees can accept ‘knowledge’ and ‘knowledge management’ concept or

not?

5.

Financial return possibility, like self of KM or corporate whole benefits

return.

Knowledge

performance can be measured in two categories (van Buren, 1999). One is

financial performance. However, financial assessments such as ROI are

particularly difficult to make for KM activities. The other is non-financial

measure including operating performance outcomes and direct measures of

learning. Examples of operating performance measures include lead times,

customer satisfaction, and employee productivity. Learning measures include such

items as the number of participants in communities of practice, employees

trained, and customers affected by the use of knowledge.

A

measurement model for knowledge

Businesses are

increasingly concerned with knowledge and managing the knowledge that they have

within their organization. On the basis of the theoretical insights and

understanding of the challenges facing companies worldwide, Lim,

Ahmed, and Zairi, (1999) posit a model to facilitate monitoring and

tracking of progress so as to allow leveraging of positive effects from managing

knowledge. They propose a model founded upon a continuous improvement

methodology. The model utilises a Deming type PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycle.

They explain below what each of these of these terms connotes with respect to

managing knowledge:

(1)

Capturing or creating knowledge (plan).

(2)

Sharing knowledge (do).

(3)

Measuring the effects (check).

(4)

Learning and improving (act).

In order to operationalise

the model it is necessary to define the key areas that an organisation must

direct attention so as to capture all aspects for effective knowledge

management. These key elements are captured by Ahmed,

Lim, Zairi (1999) proposed a COST model (figure2-11), which is

elaborated next. In essence there are four perspectives to look at:

Customer:

what can we learn from our customers? How can we learn from our customers? How

can we become effective in learning from our customers?

Organization:

What are the key skills needed to make the business a success? Who has these

skills? How are these skills harnessed, and shared? How are we doing compared to

other organizations?

Suppliers:

how are our supplier links? Does the organization obtain an optimum quality,

cost and delivery service from the suppliers? Does the organization conduct

supplier quality programs?

Technology:

how many computer terminals (which are hooked up for information transfer) are

available per employee? And are these links being used effectively within the

customer-organization-supplier?

Figure 2-11: COST model

Source:

Pervaiz K. Ahmed, Kwang K. Lim, Mohamed Zairi (1999)

Combining the COST model

and the four steps for KM, Ahmed, Lim, and

Zairi (1999) obtained the matrix outlined in (figure2-12).

This matrix helps in

obtaining a deeper understanding of how KM affects the

organization as a whole and it also prompts practitioners to look at all

the various aspects of implementing KM. It forces the practitioner to consider

all factors, "soft" as well as "hard" factors and it also

forces managers to link KM to the overall organization's policy and strategy. It

also allows managers to list out the important functions that support knowledge

management and to prioritize them. The suggested measures are by no means

complete, but we list them as a catalyst for mangers to think of other measures

that are suited to their organization's current environment

(Ahmed, Lim, and Zairi,1999).

Customer

matrix

By comparing horizontally

across the matrix, the user can be prompted to think of further measures that

would indicate the success or failure of KM activities. These could include:

1.

customer satisfaction;

2.

customer retention;

3.

customer relations.

Organization

matrix

Organization

matrix is to give people a process to create new

knowledge, hence measures could include; number of workers participating in

process and number of workers rotated. Other measures that look at the cultural

aspect of behaviours and attitudes that support the environment of trust and

collaboration, hence a measure to ensure knowledge is being captured and shared

effectively is much needed.

Supplier

matrix

This is part of the

knowledge exchange that very much forms the foundation of knowledge management.

Measures which maybe useful include:

1.

supplier meetings;

2.

supplier development programmes;

3.

benchmarking activities between suppliers.

Technology

matrix

Is there an overload of

information? Is all of it relevant? How can we "police" the

information posted out, in terms of the accuracy of information? (Ahmed,

Lim, Zairi, 1999)

In sum, measuring

knowledge is vital for companies to ensure that they are achieving their goals.

Measurement provides an important mechanism to evaluate, control and improve

upon existing performance. Measurement creates the basis for comparing

performance between different organizations, different processes, different

teams and individuals.

A linkage between

strategy, actions and measures is essential and unless companies adapt their

measures and measurement systems to facilitate compatible introduction

implementation will fail to reap the expected benefits (Dixon et al.,

1990). Critically, adoption of the wrong measures and wrong measurement system

can severely circumvent performance. Thus care and diligence must be excercised

in the development of a measurement system for programs such as knowledge

management, since dysfunctional penalties of an inappropriate system can be

extremely heavy.

In

this Paper, the scope of research would be solely on secondary data review. It

include reviews of books in libraries, downloaded articles from reputable

journals and searches over the Internet for useful websites and information.

Through literature review and critique, the study developed some improvement KM

model and integral models for SMEs to better implement KM.

4.Critique

4.1

How knowledge is to be managed? What is suitable definition of KM in this study?

Knowledge

management is a specification of management as such now we know what knowledge

is and we know what management is. It is now time to look at what it means to

manage knowledge. Beijerse (1999, 2000) defined management as the

strategy-driven motivation and facilitation of people, aimed at reaching the

organizational goals, and defined knowledge as the capability to interpret data

and information through a process of giving meaning to these data and

information. When we look at this definition it becomes clear that knowledge

management is somewhat more specific than management as such. Whereas management

focuses on motivating and stimulating people, knowledge management focuses on a

certain aspect of people, i.e. their knowledge.

A

common definition of KM is: "The collection of processes that govern the

creation, dissemination and leveraging of knowledge to fulfill organizational

objectives". KM is an emerging set of organizational design and operational

principles, processes, organizational structures, applications and technologies

that helps knowledge workers dramatically leverage their creativity and ability

to deliver business value. In fact, KM is about people and the processes they

use to share information and build knowledge (Hanley, 1999). Marshall (1997)

considered that KM refers to the harnessing of "intellectual capital"

within an organization.

KM

focuses on "doing the right thing" instead of "doing things

right". In my thinking, KM is a framework within which the organization

views all its processes as knowledge processes. It is important to notice that

knowledge management here does not refer to information technology only.

Attention is also being paid to strategic, personal, organizational and cultural

aspects, which are at least as important as the technological side of the story.

With this in mind, here defines knowledge management as "arranging and

managing the operational processes in the knowledge value chain in such a way

that realizing the collective ambition, the targets and the strategy of the

organization is being promoted".

4.2

Integrated improvement models for KM

In practices of reviewing exist

literatures and case studies, what are their strength and weakness. The study

derived some useful theories and practices model for SMEs, and try to build some

improvement models as following:

The

gap fulfilling-COST model of Knowledge chain management

The first model

is the gap fulfilling-COST model of Knowledge chain management (Figure 4-1):

Knowledge is like

a river, it must be flowed smoothly in corporation just can increase knowledge

sharing and further transfer, apply, innovate and reuse knowledge to be a cycle

to recreate new knowledge. Therefore, the aim of the study here is to find out

the gap and to fulfil it to link knowledge flows to build a bridge and to

construct an integrated KM mode for SMEs. I propose five solutions to narrow and

fill gaps between knowledge seekers and providers as follows:

Gap1:

between knowledge entry and creation (solution: Motivation,

inspiration, pure chance, interaction, developing new knowledge, improving

existing knowledge or by getting rid of knowledge that is out of date or has

become irrelevant and buy-in. I.e. learning, teaching & training,

interaction of interpersonal and people-machine, outsourcing)

Gap2:

between knowledge

creation and diffusion (solution: interaction,

collaboration, and communication. I.e. knowledge database and community.)

Gap3:

between knowledge

diffusion and transfer (solution: communication and

trust. I.e. social intercourse and community of practice)

Gap4:

between knowledge transfer and knowledge application (solution: commitment and

sharing. I.e. partnership, strategic action and sharing best of practice.)

Gap5:

between knowledge application and innovation or

reusing (solution: independence and cooperation, incentive. I.e. teamwork and a

clear & definite incentive measures.)

Furthermore, for creating

core competences, knowledge flows need to add value through COST model, then it

just useful and helpful to corporations to produce core competences. It also

means producing corporate intellectual capital (IC).

"Turning knowledge into action" is a unique way to fill gaps of

knowledge creation to diffusion to transfer to application.

Therefore, how to manage knowledge effectively and practice knowledge in

corporations first needs to fill knowledge gaps for smoothing and accelerating

knowledge flows, second needs to measure KM performances and to reach corporate

core competences to through COST (Customer,

Organization, Suppliers,

Technology)

model.

Customer:

customer satisfaction; customer retention; customer relations.

Organization:

Number of workers participating in process to create new knowledge and number of

workers rotated, cultural aspect of behaviors and attitudes, trust and

collaboration.

Supplier:

supplier meetings; supplier development programs; benchmarking activities

between suppliers.

Technology:

overload of information? Is

all of it relevant? How can we "police" the information posted out, in

terms of the accuracy of information? Reduces the cost of development of a new

product/service; increases the productivity of workers by making knowledge

accessible to all employees; therefore increasing employee satisfaction.

Figure

4-1: The gap fulfilling-COST model of Knowledge chain management

Because

of knowledge flows focus on action and operationalizing knowledge, that notion

centers on a starting point for Pfeffer and Sutton: even though we know so much

and are smart in developing great concepts we often benefit from it only

marginally, because of failure in putting knowledge into action. Perhaps a

heritage of the Taylorist distinction between knowing and doing in the

organization of labor? Interestingly, Pfeffer and Sutton (2001) explain how

typical knowledge management practices may make knowing-doing gaps wider. A

focus on technology and transfer of codified information, limited possibility to

transfer tacit knowledge using formal systems and lack of understanding of the

actual work among knowledge managers (staff department, etc.) are among them.

Thus knowledge should be a responsibility of everybody and basic ICT

(Information and Communication Technology) infrastructures are not enough.

A

central underlying notion from Pfeffer and Sutton is that knowledge is not

easily transferred within and across firms. Memory/heritage, fear, measurement,

and internal competition hamper putting knowledge into action. Even though the

focus is on closing the gap and untapping the human potential the analysis

covers somewhat more don'ts and how things go wrong than it offers guidance for

KM.

When

an employee gets sick, his or her knowledge is unavailable for the company for a

certain amount of time. In some cases, especially in small companies that depend

on each employee, such situations can become threatening to the overall

operation. The only effective way to prevent such knowledge gaps is the

systematic training and rotation of employees in complementary divisions. Only

if other employees are able to take over, without a long period of "having

to figure out how to do the job", can smaller companies survive the

unpreventable short-period loss of an employee.

Modified

knowledge value chain model

For

fill the knowledge gaps, in practice, we can use the four main aspects of the

knowledge value chain - i.e. determining the knowledge gap (between needed and

available knowledge), developing and/or buying knowledge, sharing knowledge and

evaluating (the use of) knowledge As figure 4-7 illustrate in the model: First,

the strategic need for knowledge needs to be determined. Second, the knowledge

gap needs to be determined. In the third place, this knowledge gap needs to be

narrowed by developing new knowledge, by buying knowledge, by improving existing

knowledge or by getting rid of knowledge that is out of date or has become

irrelevant. Fourth, the available knowledge is disseminated and applied to serve

the interest of customers and other stakeholders. It is important to notice that

knowledge management here is combine knowledge chain and two kind of knowledge

value chain to increase KM performance and form a cyclical continuous process.

Figure

4-2: Modified knowledge value chain model,

Source:

modified from Mathieu Weggeman (1997), Ching Chyi Lee and Jie Yang (2000)

4.3

How these mixed together for SMEs to implement KM successfully?

Establish

the linkage of management of knowledge and corporate process and strategy in

organizational perspective, like knowledge chain, knowledge value chain, and the

integral KM models for SMEs developed in literature review, all for smoothing,

accelerate and adding value for SMEs to implement KM successfully. Which aspects

have been deeply researched from point, line to plane and from theory to

practice.

An

integral KM model for SMEs

Figure

4-3: A more complete framework for the KM

implement in SMEs

The

KCM and KVC have been developed to assist organizations to understand the range

of KM options, applications and technologies available to them. The KCM and KVC

is a model, which helps organizations understand KM in its broadest sense. It

provides a view of the totality and complexity of the various KM theories, tools

and techniques presented in the literature. It also provides a framework in

which management can balance its KM focus and establish and communicate its

strategic KM direction. Whether taking an organizational, national or global

view of knowledge management, the question will remain: “What is the right mix

of KM-related investments now and for all of our tomorrows?”

Organizational

conditions, attitudes, decisions, and activities believed to be crucial for

effective knowledge management in organizations can be classified in six

categories or factors: the balance between the need for knowledge and the cost

of knowledge acquisition; the extent to which knowledge originates in the

external environment; the internal knowledge-processing factory; internal

knowledge storage; use and deployment of knowledge within the organization; and

attention to human resources in knowledge processes (Klobas, 1997).

Obviously

it is important to examine what knowledge can relate to in an organization. In

principle, one should have knowledge of everything, but from a viewpoint of an

analysis of the organization, it is expedient to define a number of so-called

knowledge domains in which the entrepreneur can target himself in particular.

Five knowledge domains are defined here: organization, marketing, human resource

management, technology and R&D.

Knowledge

with regard to the organization has to do with things such as management,

policy, culture, internal processes, cut backs, best practice sharing, alliances

and teamwork. Knowledge with regard to the human resource management, such as

personnel, career planning, incentive knowledge sharing mechanism, When thinking

of marketing knowledge, one should think of things such as competition,

suppliers, customers, markets, target groups, consumers, clients, users,

interested parties, sales, after sales, trade and distribution and relation

management. When thinking of technological knowledge, one should think of

technological development, information and communications technology,

knowledge maps; knowledge databases

and e-Business. When thinking of R&D knowledge one should finally think of

knowledge of products, research and development, core competencies, product

development and assembly.

5.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While

many published anecdotes celebrate the success of knowledge-management efforts

in large companies, there are clearly many methods for achieving success in SMEs

as well. Technology has in many instances leveled the knowledge-management

playing field. However, there are also many conventional knowledge-management

techniques that afford additional gains for SMEs. On the other hand, SMEs have

the overwhelming advantage of being intimate and, since knowledge management

initiatives live from the buy-in of knowledge holders within the company, this

fact makes SMEs the perfect place quickly and effectively to try some of the

techniques because buy-in can be generated without as much effort as is needed

in bigger corporations.

Many

projects can be started at a grass-roots level, with employees gaining

enthusiasm quickly because results can be realized in a short period of time.

One key employee can often lead the whole company through an initial